Mika Elo: Outi, you are known as a performance maker, and you Rosie, as a composer and musician. I was expecting that your work might challenge the viewer; and so it does: there is nothing to see. Your work is a sound piece to be listened with wireless headphones while walking around in the exhibition. In a way, there is nothing for a viewer, but, at the same time, the piece is very visual as it triggers one's imagination. It feeds the mind's eye. What kind of experience you think your work might afford in an exhibition focusing on photography?

Outi Condit: We started off with the idea of the listener becoming the medium, the bearer of images that may not be there to look at but still somehow manifest not only in their imagination, but also in their body. Originally we planned to play more overtly with the listener becoming the visual element of the piece by introducing invitations and instructions in a participatory performance kind of way. But we also didn't want to make the piece feel bossy or uncomfortable for the listener. So, we opted for a more subtle approach through humour and rhythm, which also produce perceivable embodiments, people jiggling along or laughing (we hope) as they listen–this came of course naturally to Rosie, who is a composer who works with comedy.

Rosie Swayne: We were excited by the idea of exploring how photography operates with and through human bodies, histories and politics. It felt fitting to delve into this in a non-visual way, with the hope that we inspire the audience to contemplate the embodiment of photography in an internal, physical and mental sense.

ME: Outi, your artistic research deals with the affective, discursive, bodily, and technological framing conditions – apparatuses – within which an actor works. This implies various collaborations. You have addressed this for example the multilayered performance The Actress (2017) conceived and realized in cooperation with theatre director and visual artist Vincent Roumagnac. You have also developed elements of a 'networked actor theory' and a peculiar performing apparatus 'remote control human' that involves various forms of co-writing and co-acting. Now, your and Rosie's piece is entitled Within the apparatus. What kind of apparatus does it address?

OC: Neither of us comes from photography or visual arts so in many ways our approach was quite different from that of my research, where I'm deconstructing my own home so to speak. But here we bravely took on apparatuses related to photography, looked at their histories and technologies, and speculated on their politics and bodily affects. When we started working I think we had at least five different paths of interest: the materiality of analogue and digital photographic processes and their algorithmic afterlife, the spiritualist movement's involvement with early photography, racial bias embedded in photographic media and hardware, and the politics of archives–I'd recently read Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments where she reads archived images "against the grain" to uncover marginalized histories, and I was completely blown away by it. All these themes are in one way or another still present in the three complimentary audio pieces of the finished work. On the piece titled Caught in the Medium Ep. 14: Racist Cameras we were fortunate to be able to work with writer, historian Marjory Morgan, who recently wrote an article titled The Black and White Truth About Photography and who also happens to be Rosie's friend from way back. In my research I look at how ‘bodies’ and ‘apparatuses’ co-construct and leak into each other. In this work we hope the listener gets a bit of a bodily feeling of how photographic media may mediate the world, perception, and social lives, affecting different bodies differently. Listening is corporeal and intimate after all, and Rosie's an amazing composer.

ME: 'Composition' is something that is at the core of artistic work independently of the art form. The understanding of what is at stake in 'composition' might, however, vary depending on the approach and artistic medium. Photographic composition is often thought of in terms of framing a view. Rosie, what is 'composition' for you?

RS: It’s an interesting question in the context of this piece because Summoning the Archivists really caused me to interrogate the notion of composition and what being a composer is. I had more false starts than I have ever encountered in the composition of a piece of music/sound art in my life, and weeks and weeks went by when I was saying to Outi “I can show you a draft in 2 days - it just doesn’t sound like what I’ve written in my head yet” I had such a strong sense of what it *should* sound like, I had what I felt was a strong concept, structure and all the “ingredients” and yet the sound world I could hear in my head was not manifesting on audio–it was disturbing! It felt like an enormous collaboration, not only with Outi but also the words of so many archivists who had in turn been informed by 150+ years of work by all kinds of photographers, and also the sounds of cameras invented through the ages, sourced by watching hours of YouTuber enthusiast collectors, waiting for the much valued moment when they press the shutter (and hopefully don’t talk when doing it!). It was a process that was super exciting but also somewhat overwhelming–I think it’s quite usual for artists of any sort to get to the stage where they are worrying they have got “lost in the process” and I had the strong feeling that I was not composing at all, just flinging a bunch of sounds in the air and hoping for an “infinite number of typewriters” moment–very different to how I operate usually. In hindsight I can appreciate that this was, in actual fact, probably composition.

ME: When listening the piece–which I appreciate as a composition–I can sense that there is a multifaceted working process behind it, but I never came to think of the enthusiast camera collectors' videos as the possible source of the triggering sounds! What I knew, instead, was that in the process of preparing the piece, you dug into the archives of the museum. What were you looking for and what did you find?

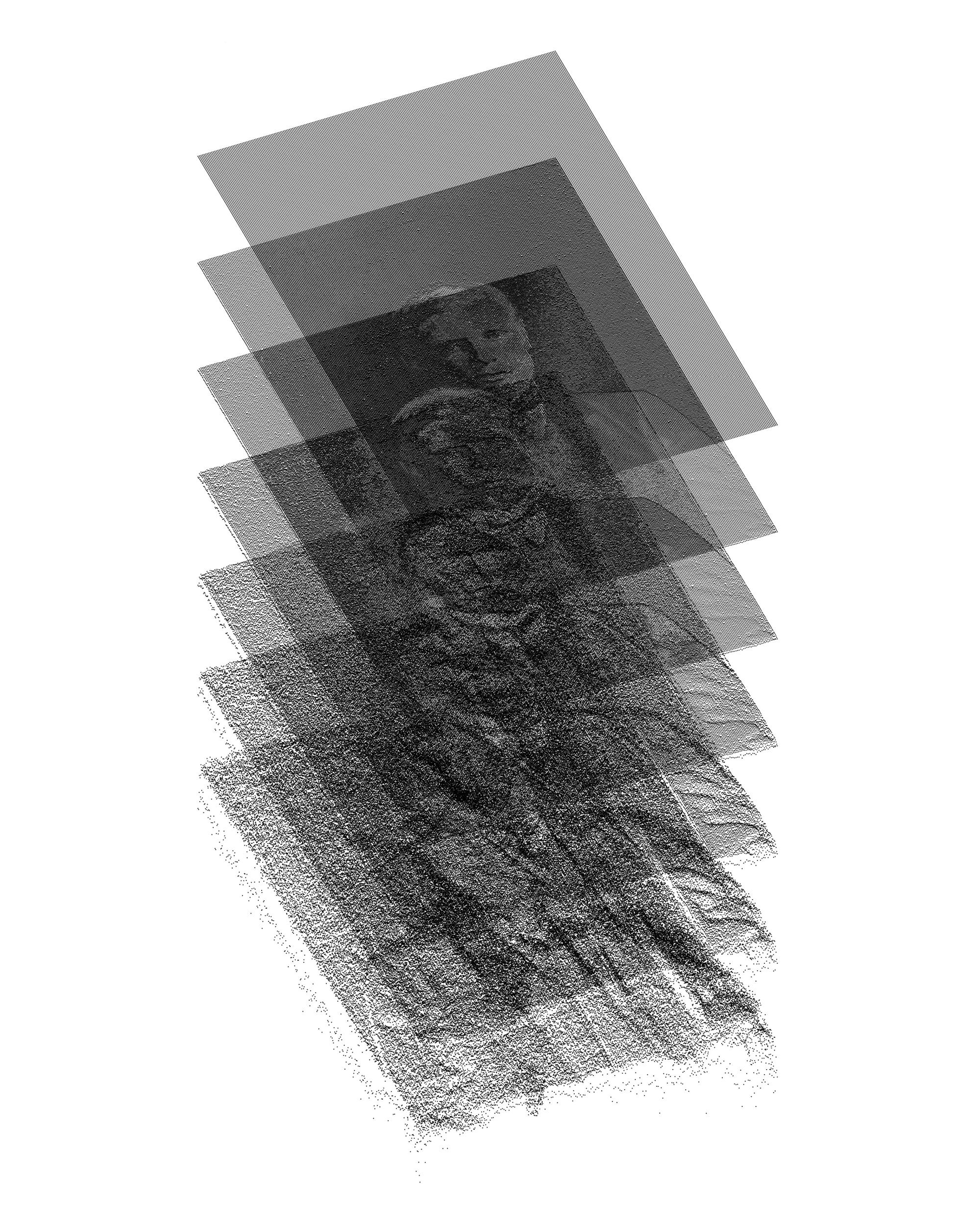

RS: We wanted the work to be site-specific, so working with the museum archives followed from there. I found them a great insight. Summoning the Archivists was inspired by my first visit to them–curator Sofia Lahti showed me the archive’s database on a computer, which for some reason was not functioning properly that day–so instead of each archive entry in the database showing a digital image of the photograph in question, we were left only with the archivers choice of words and our own interpretation of them to form the image in our imaginations. The notion that the archivist becomes the medium in this instance was a compelling one–despite the archivists’ ethos of neutrality, the personalities and era of the individuals subtly shine through in their choice of words.

OC: Yes, they're supposed to be objective and apolitical but some of them are hilariously not. Different kinds of archivist characters started to come forth from the descriptions, for instance one with strong opinions about what’s going on and what the subjects of the photograph might be thinking. As an actor I had fun with those. And I was also touched by the archivists' labour–thousands and thousands of images documenting people's lives through the decades, wars, art, families, pets, more and more the closer to the present one comes... A lot of it also feels very familiar (often very Finnish), like I've already seen these pictures a thousand times, even though I've only ever read the descriptions. It’s like I can see their figures and shades in my mind's eye, like they're my Granny's albums and my Mom's albums, and I already carry these images within me.